How important are coral reefs to tourism on Guam?

The number of tourists has reached record levels over the last few years, at around 1.4 million tourists each year. As reported in the 2008 State of the Coral Reef Ecosystems of Guam report, “the marine resources of Guam have been consistently identified as an important draw for tourists. A tourist exit survey conducted during a recent economic valuation of Guam’s coral reefs shows that, on average, 28.5% of tourist sector revenues depend on healthy marine ecosystems. Coral reefs play an important role in the creation and protection of the beaches that draw tourists and in the protection of the infrastructure that support their visits to the island.” “However,” the report continues, “the coastal development required for sustaining and enhancing Guam’s tourism economy, and the overuse and misuse of the island’s coral reef habitat for recreational and commercial activities, has the potential to degrade the very resources that a substantial part of the tourism industry is dependent upon for sustained, long-term viability.”

The report states that “SCUBA diving, snorkeling and related activities continue to be very popular for both tourists and residents. According to a recent coral reef economic valuation study conducted on Guam, an estimated 300,000 dives are performed on Guam each year. Official Pacific Association of Dive Industry statistics cited in this study indicate that around 6,000 open water certifications were provided in 2004; the number of certifications provided by other organizations is not known. The number of divers and snorkelers visiting Guam’s reefs will likely increase significantly with the additional military personnel, their dependents and others associated with the military expansion.”

What are the potential impacts of diving, snorkeling, and related activities?

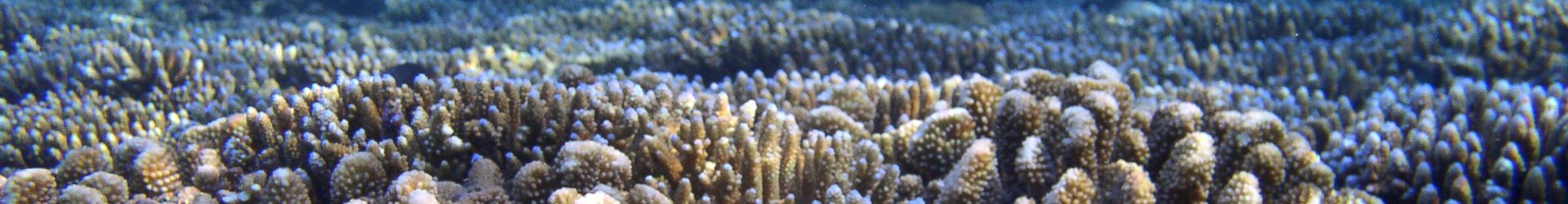

Divers, snorkelers, and those participating in related activities can directly impact the health of coral reefs by accidentally or intentionally touching or breaking coral colonies or other sensitive marine life. Corals are particularly vulnerable because their tissue can be easily damaged when even gently pressed against their razor-sharp skeletons. Check out this illustration of how touching damages coral. Injuries to coral, such as breakage or tissue damage, can have impacts beyond the broken branch or the small patch of damaged tissue. Repeated injuries to the same colony, which is not uncommon at several sites on Guam that experience high rates of use, can kill significant parts of the colony. The damage can also leave the coral vulnerable to infection by bacteria or other disease-causing pathogens. For example, an outbreak of a white plague disease was recently observed on a group of large, flat yellow finger coral colonies at Ypao Beach, in the Tumon Bay Marine Preserve. Snorkelers and swimmers have been regularly observed standing on these particular coral colonies, and while there is no definitive proof that the disease outbreak, which killed large portions of these colonies, was caused directly by the impacts of snorkelers and swimmers, the absence of the disease on nearby colonies which are not regularly used by resting snorkelers and swimmers, suggests a link. Divers, snorkelers, and others can also impact corals and other organisms indirectly by kicking up sand and silt, which then falls on nearby marine life.

How are these activities impacting Guam’s reefs?

According to the 2008 State of the Coral Reef Ecosystems of Guam report, “while the contribution of recreational users to the degradation of Guam’s coral reefs is likely considerably less than sedimentation, overharvesting of vulnerable reef fish taxa, and runoff and associate pollutants, the overuse and misuse of certain high-profile reef areas for recreational activities continues to be a serious concern . These impacts tend to be focused on relatively small, but exceptionally valuable, reef areas, and can have a direct impact on the long-term viability of the businesses that depend on these sites to draw tourists.”

As mentioned above, corals at reef sites that experience large numbers of users are highly vulnerable to injury, as they are more frequently touched or kicked by divers, snorkelers, swimmers, and others carrying out similar activities. On Guam, the reef near the Fisheye Observatory in the Piti Bomb Holes Marine Preserve, the reef near Ypao Beach Park and a few other reef areas within the Tumon Bay Marine Preserve, Hap’s Reef, Blue Hole, and a few other sites are heavily used by recreational users. For example, an estimated 50-200 dives occur daily within the popular 0.25 hectare (0.6 acre) reef around the Fisheye Observatory in the Piti Bomb Holes Marine Preserve. According to the 2008 State of the Coral Reef Ecosystems of Guam, “even a conservative estimate based on these observations suggests that the number of dives that occur at this small site each year (>18,000) vastly exceeds the 4,000-6,000 diver per year threshold value above which coral cover loss and coral colony damage levels may increase rapidly.”

But beyond simply the large numbers of people using this area, the situation is made worse because most of the divers at the Piti site and other easily accessible, shallow, protected sites are open water students or resort divers. These divers have not yet developed adequate buoyancy control skills, and are more frequently observed intentionally grabbing or accidentally kicking coral colonies or kicking up sediment. Unfortunately, the behavior of some dive guides that regularly use the reef at Fisheye results in far more damage than would otherwise be caused if they acted more responsibly. For example, these dive guides have been regularly observed instructing their customers to grab coral colonies or even to sit atop coral colonies as they pose for a picture.

Another impact readily observed at the Fisheye site, but which can also be seen elsewhere on Guam, is the trampling of sea grass and other benthic organisms by divers and snorkelers traversing the reef flat to reach their intended destination. While it is unlikely that a few people walking through seagrass on isolated occasions can have a significant impact on seagrass health, seagrass beds trampled by dozens of people each day can be noticeably impacted. In these cases, the path through the seagrass beds used by many people is readily visible as a bare patch where living seagrass once used to grow. Seagrass is an important part of coral reef ecosystems, and is used by many species of reef fish an other organisms, so any damage to seagrass can have impacts to the larger reef ecosystem.