What are crown of thorns sea stars and how do they impact coral reefs?

The crown of thorns sea star, Acanthaster planci, is a natural predator of coral, and is considered one of the most influential species in Indo-Pacific coral reef ecosystems. A single crown of thorns sea star, which can grow to over 2 feet in diameter, can eat up to 6 square meters (65 sq. ft.) of living coral each year. It is believed that under normal conditions, crown of thorns sea stars (sometimes shortened to COTS) can actually help reefs become more diverse by selectively preying upon fast-growing corals and thus creating new space for other coral species. However, outbreaks of these coral-eating sea stars – which sometimes involve thousands of sea stars on a given reef – appear to be occurring more often and may be more devastating to reefs than in the past. According to the definition used for surveys on the Great Barrier Reef, a local crown of thorns population is considered in ‘active outbreak status’ when densities reach or exceed 30 individuals/hectare (a hectare is about 2.5 acres, or roughly the size of a baseball field).

Even if the current rate and severity of outbreaks is no different than in the past, it is likely that the combined impact of numerous human-caused stressors, such as sedimentation, overharvesting, and stormwater runoff, have significantly reduced the ability of reefs to recover after being impacted by crown of thorns or other acute (i.e., short-term) disturbances such as typhoons.

What causes crown of thorns outbreaks?

If, indeed, the frequency and severity of crown of thorns outbreaks has increased in recent decades, another question must be asked – why? It is not clear exactly why crown of thorns outbreaks occur, but there are several plausible hypotheses, with the likely answer involving a combination of two or more of the proposed causes.

One of the earliest hypotheses suggests that the outbreaks are fueled by high levels of phytoplankton, which are the main food of crown of thorns larvae. Phytoplankton blooms may be caused the influx of nutrient-laden water into nearshore waters during large rainfall events, or may be a result of regional oceanographic events that bring chlorophyll-rich water close to reefs. The amount of nutrients delivered to the coral reefs by stormwater runoff has likely increased significantly as the amount of runoff has increased with the development and fertilizer use on Guam and elsewhere. With an abundance of food, a relatively large proportion of the the sea star larvae successfully recruit to the reef and begin their path to adulthood.

The results of a study conducted by researchers in Australia in 2008, which found that crown of thorns outbreaks in areas outside no-take marine preserves were 4-7 times more frequent than in no-take marine preserves, suggest that the absence of predatory fish, such as groupers, sweetlips, and trevally, may have an indirect influence on crown of thorns outbreaks. While the hypothesis has not yet been tested, the researchers suspect that there is a cascade effect within the reef fish and

invertebrate communities – by taking out the top level predators you would ultimately end up with fewer invertebrates that eat the very young, newly settled sea stars before they reached sexual maturity and participated in outbreak aggregations. Let’s follow the logic: if you remove larger fish, you would expect there to be more of the smaller fish that are usually eaten by the larger fish. And those smaller fish, such as wrasses, eat invertebrates that prey upon the very young crown of thorns sea stars. It makes sense, but hopefully work on this question will help us understand exactly how marine preserves protect reefs from predatory sea stars.

Another early hypothesis suggested that the declining number of Napoleon Wrasse, Triton’s Trumpet snails, and other predators of adult crown of thorns sea stars as a result of overharvesting has contributed to the increase in frequency and severity of outbreaks. However, there is doubt among researchers that even healthy populations of Napoleon Wrasse, Triton’s Trumpet snails, etc. would not consume enough adult sea stars to have much of an impact on crown of thorns outbreaks, and that the abundance of food for the larvae (e.g., phytoplankton) and the level of predation on the larvae have more influence on crown of thorns populations.

It is likely that each of the hypotheses described above explain at least some part of the apparent problem of crown of thorns sea stars outbreaks. Further research will help determine which factors play the most important roles.

How are crown of thorns sea stars affecting Guam’s reefs?

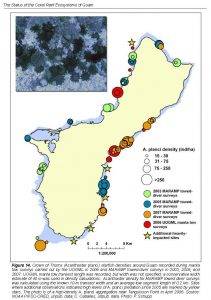

As reported in the 2008 State of the Coral Reef Ecosystems of Guam report, “Guam has recently been affected by widespread outbreaks of the crown-of-thorns sea star (COTS) since at least 2004.” Surveys conducted by the University of Guam Marine Lab between February and October 2006 at numerous sites around Guam indicated widespread crown of thorns outbreaks and large-scale coral mortality. The Marine Lab biologists observed large aggregations of the sea star, ranging from approximately 100 to over 1,600 individuals per 20-minute survey, were observed at six of 17 survey sites. Coral species preferred as food for the sea star, such as Montipora spp. and Acropora spp., were nearly wiped out at most sites, and the sea stars had begun feeding on less-preferred corals such as massive Porites spp. and Goniopora spp. An analysis of the data collected by the Marine Lab biologists indicates that crown of thorns densities of 50-61 individuals per hectare were observed on tows at three of the 17 survey sites and between 14-26 individuals/hectare at three additional sites. Most alarming, however, were observations of densities greater than 450 individuals/hectare in Pago Bay and nearly 1,500 individuals per hectare at Tanguisson Point.

The report also states that “towed-diver data from the 2003, 2005 and 2007 NOAA MARAMP expeditions provide further indication of COTS outbreaks at numerous locations around Guam over the last several years, with an increase in outbreak intensity observed with each subsequent research cruise. COTS aggregations and extensive COTS-related coral mortality have also been observed at several other sites not surveyed by the UOGML or during the MARAMP expedition. The widespread, persistent nature of these outbreaks, as well as observations of mortality among less-preferred coral species, suggest that these outbreaks have had, and are continuing to have, a severe impact on many of Guam’s reefs.”