What is coral bleaching and what causes it?

According to the 2008 State of the Coral Reef Ecosystems of Guam report, “the increase in water temperatures associated with global warming (1-2°C per century) and the regionally specific El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events are causing a breakdown in the coral-algal symbiotic relationship, which is critical to the nutrient recycling that is thought to explain the high productivity of coral reefs.” The report continues, “reef-building corals are thought to live near their thermal maxima, making them a good indicator for changing conditions, and the thermal tolerances of reef-building corals are forecasted to be exceeded within the next few decades. Small increases in water temperature, on the range of 1-2°C, cause stress to the coral host often causing them to expel their symbiotic algae.”

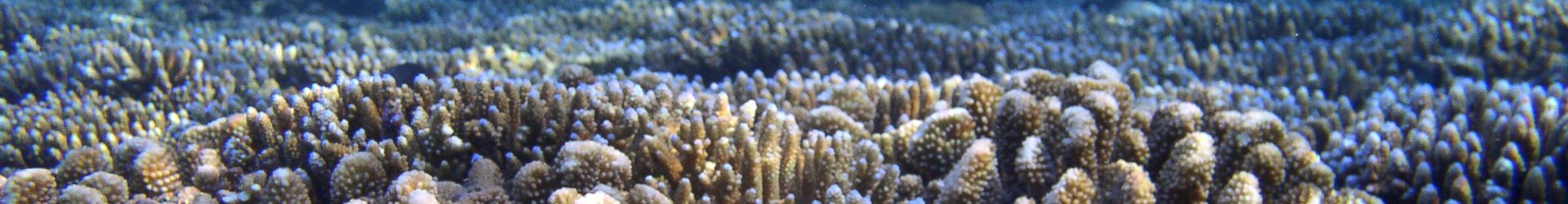

In other words, warmer than normal water is stressing corals on Guam and elsewhere, causing the symbiotic algae that live in the tissues of the coral (known as zooxanthellae) to be expelled. Because the zooxanthellae are often what give corals their color, their loss leaves the coral without color, and the white skeleton is readily visible beneath the transparent tissue. The loss of zooxanthellae can be caused by a number of factors, from warmer or cooler than normal sea surface temperatures, to

stress from sedimentation or other forms of pollution. But bleaching on a large scale – such as across reef tracts or even across an entire region – is usually the result of warmer than average water temperatures. Increased exposure to ultraviolet light, usually as a result of calm sea conditions and low cloud cover, is also believed to influence large-scale bleaching events.

What does bleaching do to corals?

Bleaching doesn’t necessarily kill the corals, but if the corals remain without their zooxanthellae for too long (e.g., more than a few weeks), partial or complete death of the colony can result. Bleached corals are left without their main source of food, provided to the corals by the zooxanthellae, which create food using energy from the sun – just like plants on land. Even if the corals don’t die of starvation, the loss of the zooxanthellae may result in slower growth rates, fewer gametes or larvae, or may make corals more susceptible to diseases or other stressors.

How will bleaching affect coral reefs in the future?

The report states that “a major concern is that the accelerating rate of environmental change, including increasing temperatures, could exceed the evolutionary capacity of coral and algal species to acclimate and/or adapt to these changes.” Basically, the ability of corals to expel their symbiotic algal partners to deal with warm water may backfire as the world’s oceans become warmer at a rate that may be too fast for coral reefs as we know them to adapt.

Thousands of square miles of reef can be affected by a bleaching event, with many important shallow water coral species killed and replaced by algae. The result is an overall decrease in ecosystem health, slowed or halted reef growth, and a severe loss in habitat for reef fish and other organisms. The report continues, “six major coral bleaching events have occurred since 1979, with massive coral mortality affecting reefs around the globe (Hoegh-Guldberg, 1999). The constantly increasing temperatures associated with global warming are likely to increase the frequency and magnitude of coral bleaching events”.

What does this mean for us?

With less coral and more algae, it means much fewer fish to eat and sell, fewer tourists seeking attractive reefs, and reefs that can’t keep up with sea level rise and that can’t as effectively protect shorelines from erosion or buildings, roads, and other infrastructure from the devastating impacts of storm surge and flooding.

How has coral bleaching affected Guam’s reefs?

Until recently, Guam’s reefs had been spared from severe and widespread coral mortality associated with large-scale bleaching events. There were observations of minor-to-moderate bleaching in 2006, 2007, and 2008 that caused concern among managers and scientists that bleaching events may become more frequent and severe in the coming decades. According to the report, “after nearly a decade without reports of large-scale bleaching, coral bleaching was observed in September and October 2006 and August and September 2007,” with both of the events associated with with above-average water temperatures. Aerial surveys carried out by local biologists indicated that the 2007 event affected shallow (< 7 meters) corals around the island. The report states that “the effects of the 2006 and 2007 events on Guam’s reefs were difficult to properly assess, as limited resources and reef access resulted in only a handful of observations and little quantitative data.”

However, the data that was available indicated that impacts were variable, with some species affected and others not, and a considerable number of coral colonies killed in some areas, while others recovered to a healthy state once water temperatures returned to normal. Monitoring data and personal observations strongly suggest that some staghorn coral species on Guam are highly susceptible to coral bleaching, which does not bode well for the future of these important species.Prior to these events, the 2008 State of the Coral Reef Ecosystem of Guam report cites an event in 1994 as “the first large-scale bleaching event reported in Guam since the establishment of the University of Guam Marine Laboratory in 1970,” with another event reported in 1996. It is generally held that neither of these events resulted in significant coral mortality.

However, in 2013 Guam experienced the worst coral bleaching event to-date, with most coral species bleaching and some succumbing to the heat stress. Guam’s reefs experienced yet another bleaching event in 2014, and, according to a U. of Guam Marine Lab study, Guam lost approximately half of all of its staghorn coral as a result of the 2013 and 2014 events. Guam narrowly missed another bleaching event in 2016 after warm waters that had settled in much earlier than normal had cooled just enough as a result of storm activity, and just as corals were showing signs of bleaching. It is unclear if the appearance of bleaching conditions during

three out of four years is an anomaly, or if we’ve already arrived at a new normal of near-annual mass-bleaching events that some scientists’ predicted wouldn’t affect the world’s reefs for another 20-30 years. However, even if it is an anomaly, the current trajectory of human-influenced global warming of the earth’s atmosphere and oceans will mean that these high temperatures will likely arrive sooner rather than later.